Is there an ideal good posture when sitting?

There is no one perfect sitting posture, however, there are a few key principles which we can adhere to to keep our body in top form.

When we sit, ideally, we should maintain the natural S-shaped curve of the spine seen from the side (creating a counterbalancing effect which helps to distribute our weight) and our pelvis should remain in neutral – that is to say, both sides at equal height and without any tilting forwards or backwards.

This allows the base for our head to sit directly over our shoulders and the weight of our head, shoulders and torso to be spread evenly through the structures of the spine and pelvis.

When in this position, the forces travelling down through the spine and pelvis are evenly distributed through the facet joints on both sides and the intervertebral discs, along with the ligaments and muscles of the body, so avoiding any unnecessary strain on these structures.

Prolonged deviations from this kind of positioning, however, can cause issues – and it’s these that we’ll be looking at today.

Pelvic Positioning and Lumbar Lordosis (Lower Back Curvature)

When in our seated position, our pelvis provides the base on which we build the rest of our posture and so is our essential first step in achieving good sitting posture and minimising the strain on our joints, disc and muscles.

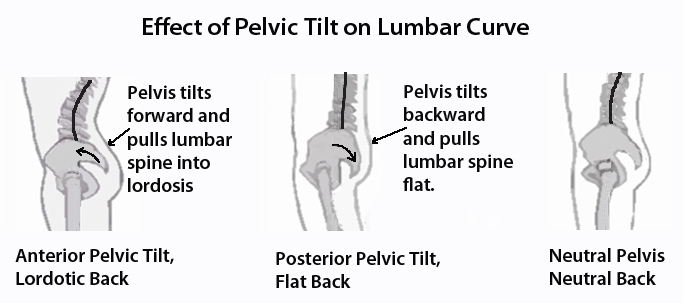

There are two fundamental mistakes made with regards to pelvic position when sitting and they both have an effect in compromising the position in which the lower back is held. The pelvis should ideally sit in what is known as neutral with the ASIS level with or slightly lower (up to an inch, depending on the individual) than, the PSIS (these are the small bony prominences which represent the highest point of the pelvis at the front and back respectively). When in this neutral pelvic alignment, the lumbar spine is able to sit in its normal gentle lordotic (lordotic meaning curved forward) curve.

However, a tilt of the pelvis posteriorly (backwards) may cause the lower back to round into flexion creating a kyphosis (so reversing the natural curve of the lumbar spine), which results in the spinal ligaments and muscles being under extra stretch and tension. There is also more pressure on the front of the intervertebral discs (IVD).

Owing to the ability of the IVDs to redistribute forces, however, the outer fibres at the back of the disc end up taking the brunt of this extra force, which can lead to damage to these outer fibres and, in severe cases, bulging of the inner discal material through the outer fibres, which can create local inflammation and, in severe cases, directly put pressure onto the delicate nerves, causing pain amongst other problems.

Meanwhile, in the reverse scenario, a tilt of the pelvis anteriorly (forwards) forces the lumbar spine to increase its natural curvature in order to keep the torso upright and balance it properly.

This extra extension (so increasing the natural curve in this area) of the lumbar spine, however, has a compressive effect on the facet joints, which can lead to irritation of the joint capsules and dysfunction of the joint surfaces, along with tightening of the muscles of the lower back leading to pain and stiffness in the movement here.

The greatest effect is often seen at the transitional area where the lower and upper back meet at the thoracolumbar junction. An increase to the lumbar lordosis causes a pivot point here, as the curvature of the spine should transition back into gentle flexion.

However, the lumbar extension will often be accompanied by extra thoracic extension, causing a pinch point where the two meet. The reverse often occurs with a posterior pelvic tilt, whereby the flexion seen in the lumbar spine is often mimicked with extra flexion into the thoracic spine, as discussed later in the rounded shoulder section, and so one long flexed spine is produced creating strain on the posterior ligamentous and muscle lines now having to take the whole weight of the torso.

These two aspects of the posture, the pelvic tilt and resulting lumbar lordosis, along with the thoracic curve and head position, tend to reflect each other in the manner mentioned above. Anterior pelvic tilt is accompanied by excess lumbar and thoracic extension, creating a military style hyper-upright posture with excessive strain on the facet joints of the spine.

The opposite is seen with posterior pelvic tilt showing a typically slouched posture with flexion of the lumbar and thoracic spine and, alongside this, we usually see rounded shoulders and the forward head carriage, characteristic of those working slumped at their desks for long periods of time. All of this together may lead to muscle soreness, ligamentous micro trauma (meaning small injuries which accumulate over time) and excess pressure on discs.

Pelvic Obliquity (Unlevelling)

Alongside the anterior and posterior (forward and backwards) movement of the whole pelvis discussed previously, we can see side-to-side pelvic obliquity, whereby one side of the pelvic sits higher than the other.

This is often the result of a twist in the pelvis, with one side being tilted either posteroinferiorly (abbreviated to PI, meaning back and down) or anterosuperiorly (abbreviated to AS, meaning forward and up).

This is commonly caused by holding positions of asymmetry for long periods, e.g. sitting with legs crossed or sitting on a wallet, wherein the pelvic position is in an altered stationary position for a long time and the supporting structures adapt correspondingly and create a more permanent position.

The resultant shift creates an extra compressive force on the sacroiliac joint (SI) of the AS side, causing irritation here, and may lead to sprains of the SI and extra tension on the hip flexors on the PI side, which has a knock-on effect on the myofascial (muscle) lines connecting the pelvis and trunk to the arms.

This tightening can also affect the insertion of the hip flexors onto the lumbar spine, pulling the spine out of its normal alignment into rotation and slight extra extension on one side.

Hip Angle

One final important consideration of sitting posture is the angle at which the hips sit. Whilst standing our hips will ideally sit in a neutral position closer neither to our front/abdomen or to our back, when sitting our hips are moved into flexion (meaning they come closer to the trunk) for long periods of time.

The result of this is an adaptive shortening of the hip flexors (the muscles on the front of the abdomen/thighs), which brings the legs up towards the body) and can cause pain in the groin area and affect spinal and pelvic functionality.

We discussed above the effect of shortening of the hip flexors as a potential cause of pain, as they will pull the spine in extension, causing extra compression of the joints and shortening and stiffness of lower back musculature.

The other result of this is that we compromise our ability to properly extend at the hip (the motion of bringing the straight leg up behind the body without any movement of the pelvis or torso). Without this movement, our body resorts instead to increased extension of the lumbar and thoracic spine as a compensation method and so creates extra movement and compressive forces at the facet joints here.

The ideal position we can adopt to minimise this effect is to try and have our knees below the level of our hips when we sit so our hip angle is at roughly 100 degrees with feet flat on the floor. Ideally, we should get up and move regularly and, if moving around is not possible, try alternating sitting or kneeling every 15-20 minutes, as kneeling opens the hip angle and so will help avoid this shortening effect on the hip flexors.

3 Ways to Improve Your Sitting Posture

Now that we’ve grasped the vast amount of time we spend on our buttocks and the effect this has on our body, we can see there’s a definite need to become aware o,f and take control of, our posture.

If you’ve read this far, you’ve taken the most important first step in becoming aware of your posture and, by implementing the few key changes below, hopefully, we won’t have to meet in person:

- Sit with the pelvis in neutral and avoid overarching or rounding the spine.

- Keep the pelvis in equilibrium side-to-side by avoiding sitting with legs crossed/on wallets, etc. – remember, your body loves symmetry, so symmetry is always the goal.

- Have the knees below the hips when sitting, so the hips are nice and open and keep the feet flat on the floor.

Book an appointment with Bodymotion today

Our team of chiropractors and massage therapists are on hand to answer any questions you may have, so get in touch today via enquiries@body-motion.co.uk or on +44 (0)20 7374 2272.

Get Seen Today – Check Availability Now

Glossary of Terms:

Flexion – The movement of two body parts coming towards each other, when discussing the spine flexion relates to the front of the torso coming closer to the front of the pelvis/legs.

Extension – The movement of two the body parts away from each other, when discussing the spine extension relates to the front of the torso getting further away from the front of the legs/pelvis and so correspondingly the back of the pelvis/legs comes closer to the back of the spine.

Lordosis – Natural curvature of the spine, whereby the spine has a mild forward curve, seen in the lower back and neck.

Kyphosis – Natural curvature of the spine whereby the spine has a mild backward curve, seen in the mid back.

Anterior – Relating to something that is forward in position.

Posterior – Relating to something that is backward in position.

Inferior – Relating to something that is lower in position.

Superior – Relating to something that is higher in position.